Diana is a gracious force. A business woman with the soul of an artist. Or an artist with a career in business. Both are valid. Her determination and perseverance inspire you to reach for the impossible, while her serene composure and grace can tame your wildest demons.

Diana has only entered my life a few months ago, and yet there are so many things I could write about her already. I’ll start with the beginning. In the summer of 2020, as the world was slowly reopening at the end of the first pandemic wave, she was on a ferry, crossing the Mediterranean sea from Athens to her island of choice. She was venturing on a solo trip, perhaps looking for some answers, as her life was again at crossroads. She was sailing away not only from Athens, her home for the past decade, but also from a long and successful career in marketing. Thousands of kilometers away, at yet another sea, the North Sea, was her Greek boyfriend who had relocated with work to the Netherlands. That summer, Diana had no idea what the future had in store, but her mind was already made up: she would leave the corporate past behind and follow her passion for jewellery instead. And she would do this in the Netherlands, where she would move to be with her man. The trip to the island would be a slow goodbye to the past and a gentle immersion into the future. The ferry kept crossing the water, and Diana’s phone blinked with a notification: “Andra started following you.” “You live in Amsterdam?” she said soon afterwards. “I am also moving to Amsterdam. Very soon.”

And that is how it started.

She hasn’t moved to Amsterdam yet - and we have a pandemic and subsequent lockdowns to blame for that - but is now indeed living in Rotterdam with Konstantinos. In the short time since she came to the Netherlands, she has already put in motion her dream company, The Sense of Beauty, an online gallery where she curates jewellery crafted by independent designers, the same way art is curated in galleries around the world. Because this is exactly what jewellery is to her: art.

I am glad that she accepted to be part of “A Day in the Life of” series, a corona-customised edition of it in fact, with no visits to shops, restaurants, or any other busy locations in town - although Diana does share her favourite addresses with me - instead with long chats in the comfort of her stylish home in Rotterdam fuelled by coffee and wine, with photos, lots of photos because she is extremely comfortable in front of the camera, a walk in her favourite area in the city, and a home-made dinner prepared for the occasion.

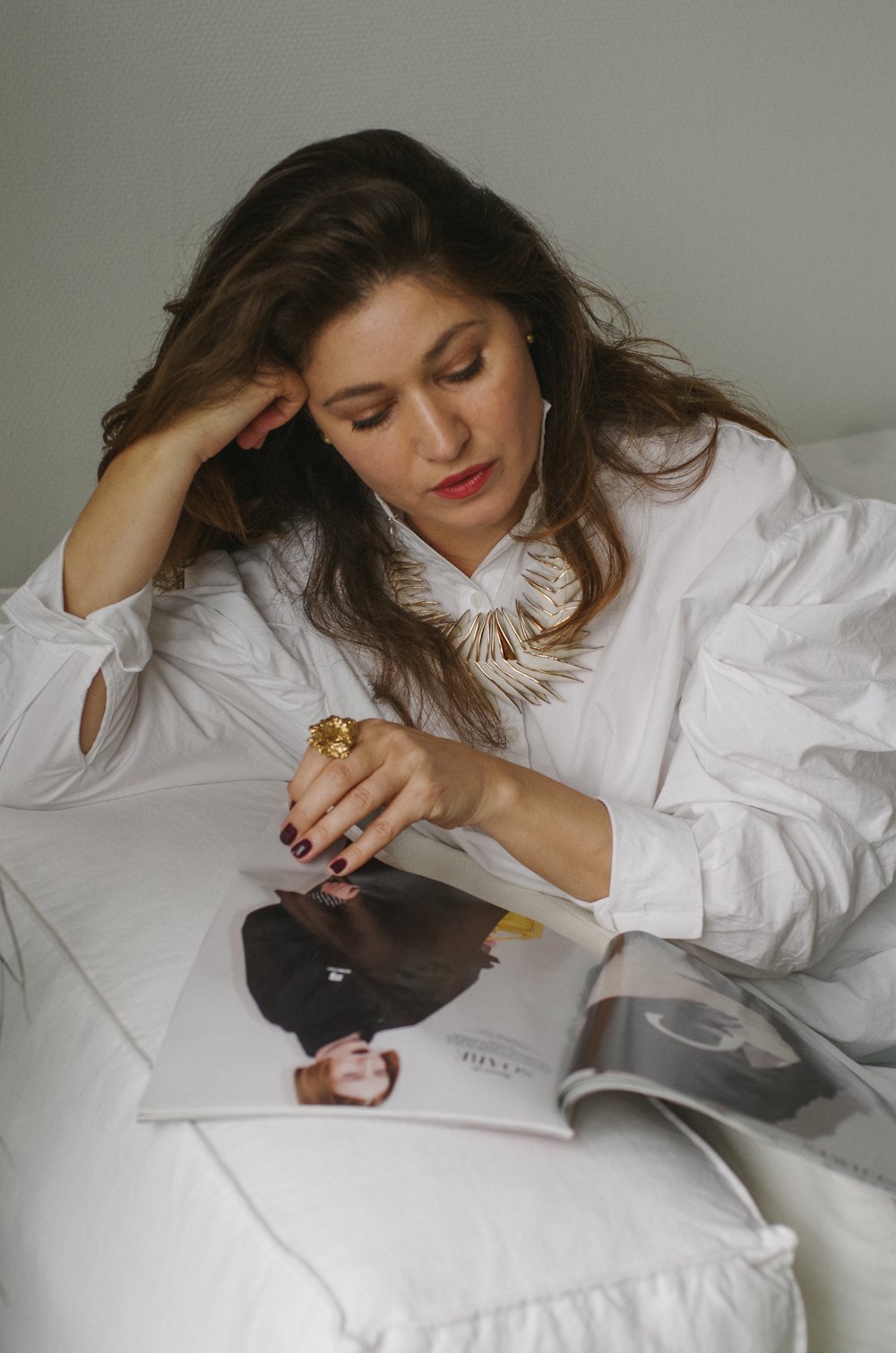

It’s a gloomy Sunday in November when I visit, but it all turns bright the moment she opens the door. She is wearing a long white shirt over a pair of leathery leggings, comfortable heels, and a state of the art porcelain necklace around her neck. Simple clothes, statement jewellery - her style.

“You are beautiful,” I say as we hug, which is becoming my custom greeting for her, an impulsive reaction to her elegance and freshness. She compliments me for my perfume, which by now I understand that she likes a lot.

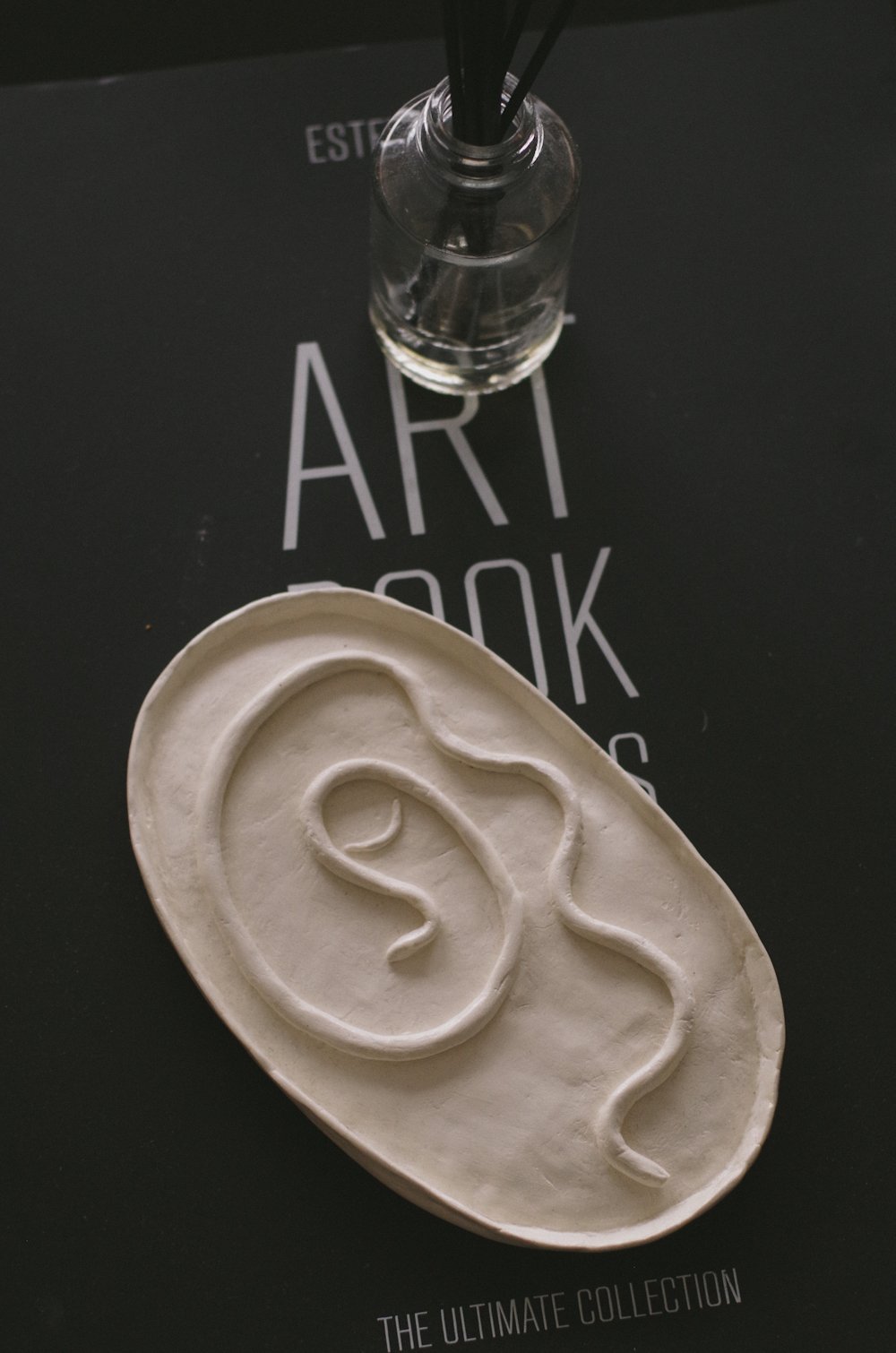

We go to the living room, where a sense of transparency and lightness envelops you the moment you step in. The room faces the waterfront through an entire wall made of windows. A glass wall. Next to it, a glass dining table with transparent, glass-like chairs. Diana makes coffee and lays the two cups on the small table in front of the sofa on which we sit. The coffee cups are transparent, too. By the force of this simplicity, it all stands out in Diana’s home, as it would in a gallery, quite a delight for the senses: the ceramic face masks on the coffee table, the large canvases in soft orange tones placed against the wall on each side of the sofa, the lamp in the shape of a flower that illuminates one canvas, the lamp in the shape of a hat next to the television, the vase in the shape of a head moulded in white porcelain from which an abundance of lilies burst above the dining table. She explains that everything I see was shipped from her apartment in Athens, and I remember that apartment well, from her social media, a classic home of high ceilings and Parisian-style wooden floors, decorated in what I now understand is Diana’s signature style.

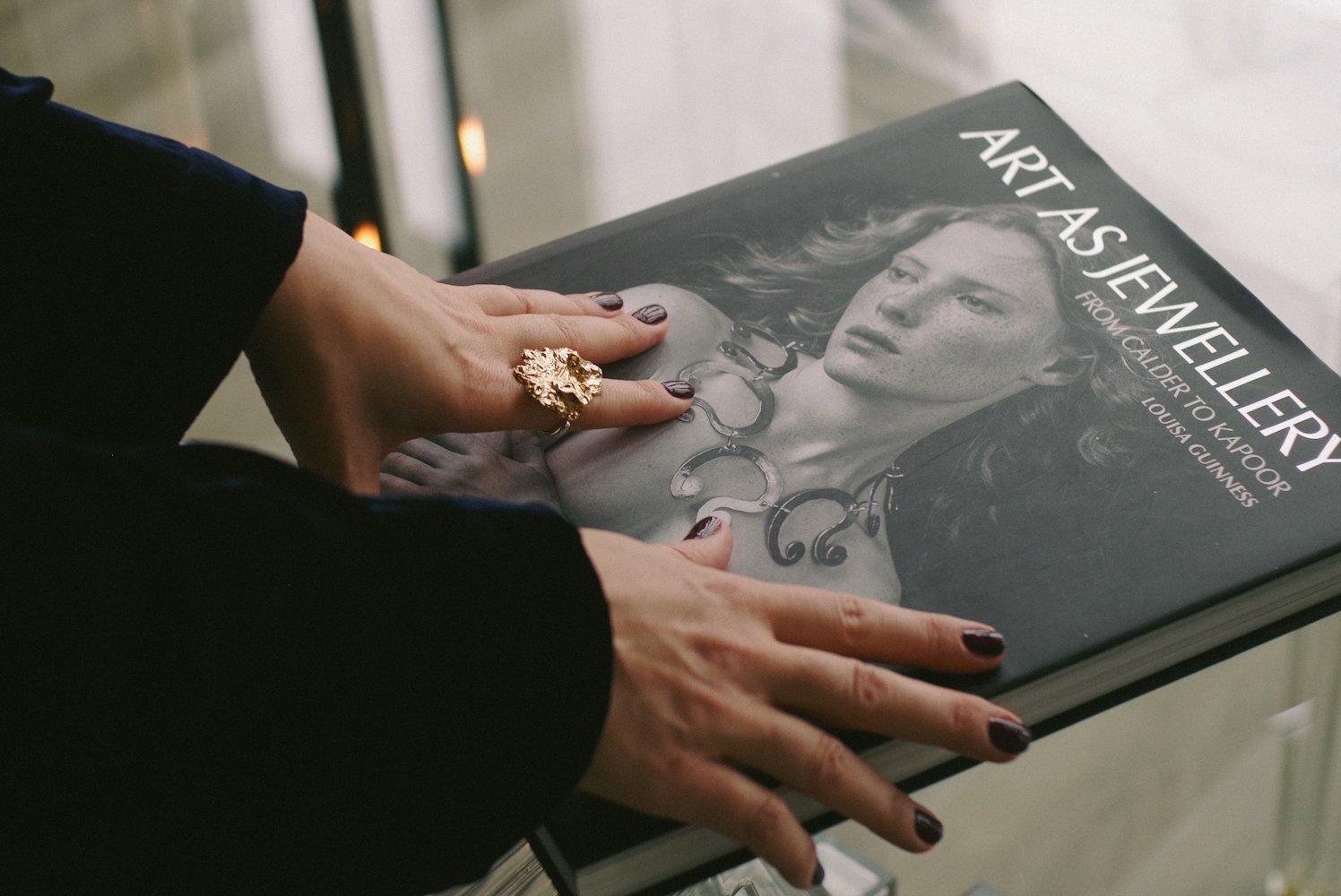

“Wait, I have something for you,” she says and disappears in the other room. She returns to the sofa with a little black box tied with a ribbon. I open it and inside is my absolute favourite ring from her jewellery collection, the Heritage golden ring. It looks even more beautiful in reality. I put it on my finger, totally charmed.

“It’s one thing for a man to give you a ring,” I say, “but to be offered a ring by a woman, wow, that feels really special!”

“It looks good on you.” I can tell she is happy to see me so excited about the ring.

“I love it! I thought I was not made for jewellery, but you just proved me wrong.”

I ask who the designer is and am surprised to find out that she designed the ring herself, inspired from some piece she discovered in the jewellery box of an old acquaintance. In fact, the entire Heritage collection is inspired by this. I am speechless. The ring feels even more precious now and I think I start to understand Diana's passion for jewellery and what she means when she says that jewellery is good for the soul, is emotional, and touches the senses the same way art does.

“I also brought you something,” I say, getting two chocolate letters from my bag, a “D” for her, and a “K'' for Kosta. I tell her about the Dutch custom of offering chocolate letters around Sinterklaas. She hasn’t heard of it, but is excited about the letters and takes a photo of them with her phone. Her excitement reminds me of my own move to the Netherlands when I, too, was discovering little by little the customs of this country. Now that Diana is here, it feels good to see the Netherlands through her eyes.

“Dutch life remains unknown to me because there are currently no Dutch people I interact with. Right now I feel totally disconnected, and everything is still to be discovered.”

Moving to a new country, however, is not so new to her. Before Rotterdam and Athens, she also lived in Paris, her first home away from Bucharest, our hometown. Each time she moved she did it for work, adding year after year of experience to her career. But this time is different. Now, it is about her.

She shares with me her impressions about the Netherlands so far.

“The only thing I miss here is the sun. Everything else is tolerable, especially when life in the Netherlands seems so easy, from daily routines to starting a business. Here I can walk a lot or bike, and there is hardly any need to drive, except to go on weekend trips. I am charmed by the Dutch interiors, warm and cosy and with fresh flowers in vases by the window, the old city centres with their picturesque canals, and I adore this house in which we live, especially because it faces the water, and to me water is therapeutic.”

When she left the corporate life, she promised herself to prioritise those things she had neglected before: to rest enough, take care of her health, exercise daily even if it’s just going for a walk, eat healthy and take the time to enjoy the meal, do more of things she loves, take care of her relationship, spend time with inspiring people, be more present.

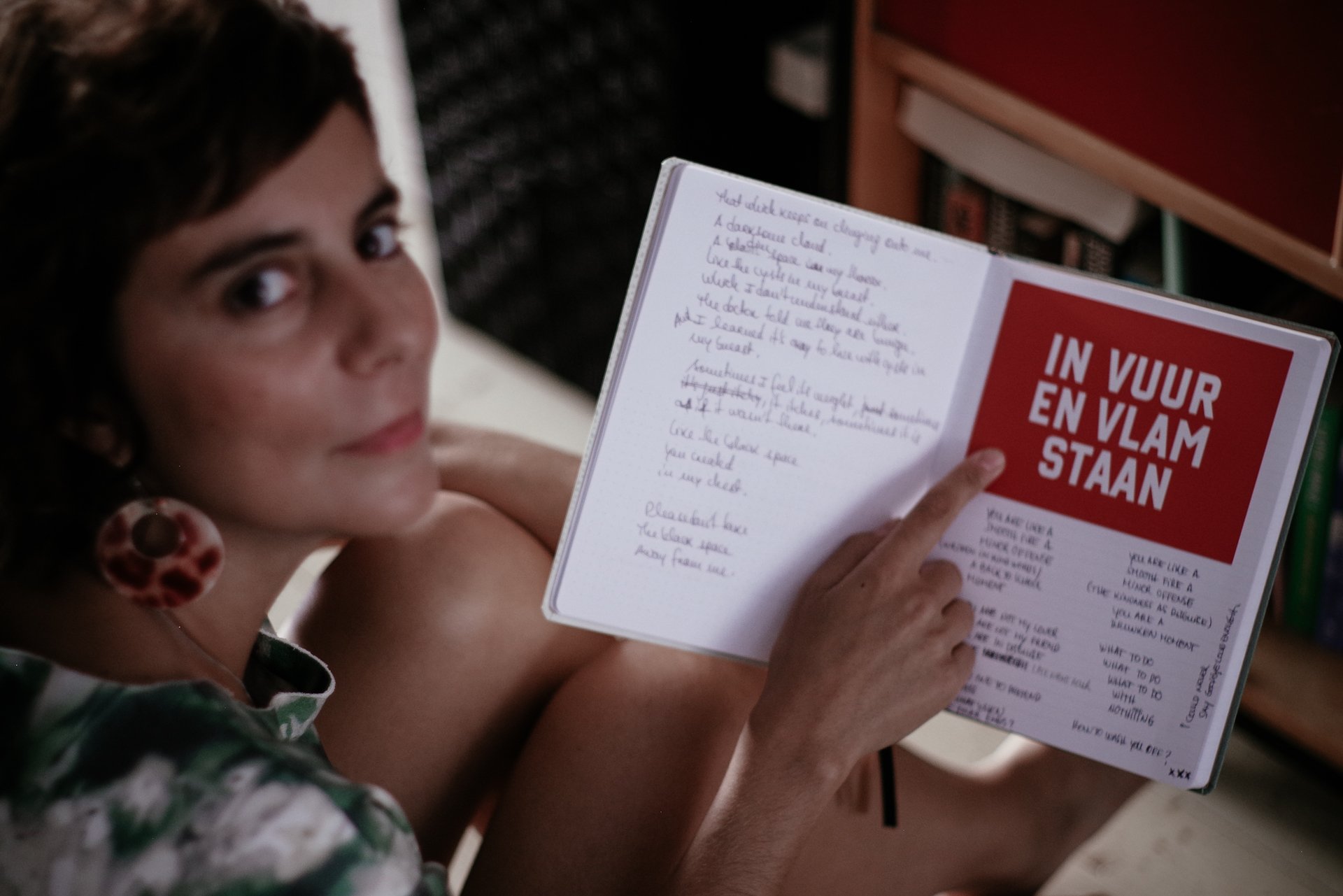

Her manifesto and her life in the Netherlands might just be one and the same thing, with jewellery as the centrepiece of her days. She starts in the morning, with coffee and a healthy breakfast of cereals, then switches to work mode. She works from her laptop, at the dining table that also serves as a desk. For lunch she prepares everything with avocado and/or sardines - both “great for the skin.” Work is important, but so are the breaks. That’s when the best ideas reach her. In good weather, a break can be a walk in the park or a visit to the flower shop. If the weather is bad, then it’s reading at home. I am interested in what kind of books she likes. Philosophy books are at the top of her list, with Way of the Samurai by Yukio Mishima and Letters to Lucilus by Seneca as favourites. Then there are the personal development, nutrition, and holistic health books. She also enjoys the magical realism works of Mircea Eliade, the absurd theatre plays of Eugen Ionescu, and the specialty theatre books, the so-called manuals for actors, such as Sculpting in Time by Andrei Tarkovsky. In the evening, after a visit to the swimming pool with Kosta and a late, Mediterranean style dinner - Greek habits die hard - it’s time for a film. A few favourites: Arizona Dream, The Piano, The Hours, A Single Man - she really admires Tom Ford’s style - and Breakfast at Tiffany's for when she feels low and is in need of a booster. Old films from the 60s or 70s are wonderful for their atmosphere, whether they are French, Italian, Greek, or even Romanian.

Theatre and cinematography have been a continuous source of inspiration for Diana and also of fascination, to the point that she thought of becoming an actress, dedicating her life to the profession. Not only did she think about it, she went for it. At that time she lived and worked in Paris. There she took acting classes to perfect her public speech and discovered that this practise had therapeutic effects, that it helped her overcome certain blockages within herself, be more outspoken and happier. She continued to take classes in Romania when she returned, and eventually applied to the National University of Theatre and Film in Bucharest. Terrified that she would be admitted and her life would change completely, she failed at the last of the four admission exams. What she felt was relief. Then came the job in Greece. After she learned the language, she enrolled at an acting school in Athens, from where she graduated a few years later.

I am amazed by her determination to follow her dreams. She is not practising acting, but I have the feeling this is far from being a closed chapter for her.

“Acting allowed for my sensitivity and vulnerability to surface. It made me aware of possessing these qualities,” she concludes.

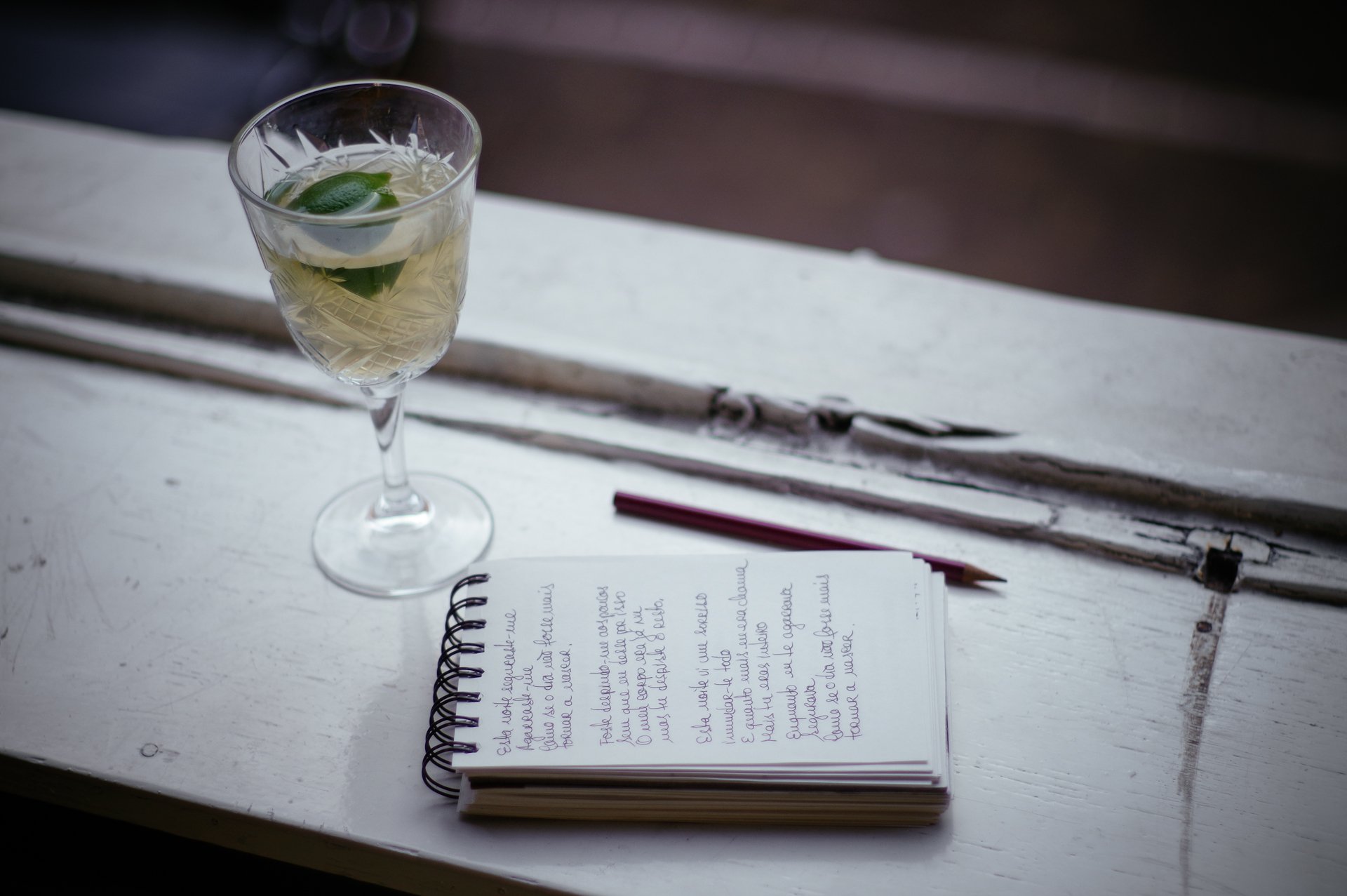

By now we are already drinking wine by the window on the mellow sounds of a radio station recommended by her best friend from Athens, and I cannot help but think how amazing this feels. Indeed, what a pleasure to be in the company of this inspiring woman, inside her Dutch-Greek home facing a canal, and not only because she is inspiring and her house is inspiring too, but mostly because in an attempt to stay safe during the pandemic many of our meetings have happened outside, in weather conditions varying from miserable to cruel. I really don’t know how we did it. How different our meetings would have been - and her whole immersion into the Dutch life - had she moved to the Netherlands before 2020. But I am really not complaining. She is here, I am here, and Sade is singing “Hang On To Your Love” on the Greek radio station.

Dutch light is scarce and clumsy, so we have to move fast if we want to take photos. I am warned there would be more outfits and different pieces of jewellery to match each of them. I am delighted to see how creative and organised she is about this. I don’t need to tell her how to pose, that is obvious from the beginning. She is not even posing, she moves and gestures naturally. “So nice that you like photos as much as I do,” I say, to which she smiles and continues to model. I know this is going to be a successful photoshoot, and my only concern is not to break anything as I follow her with my camera.

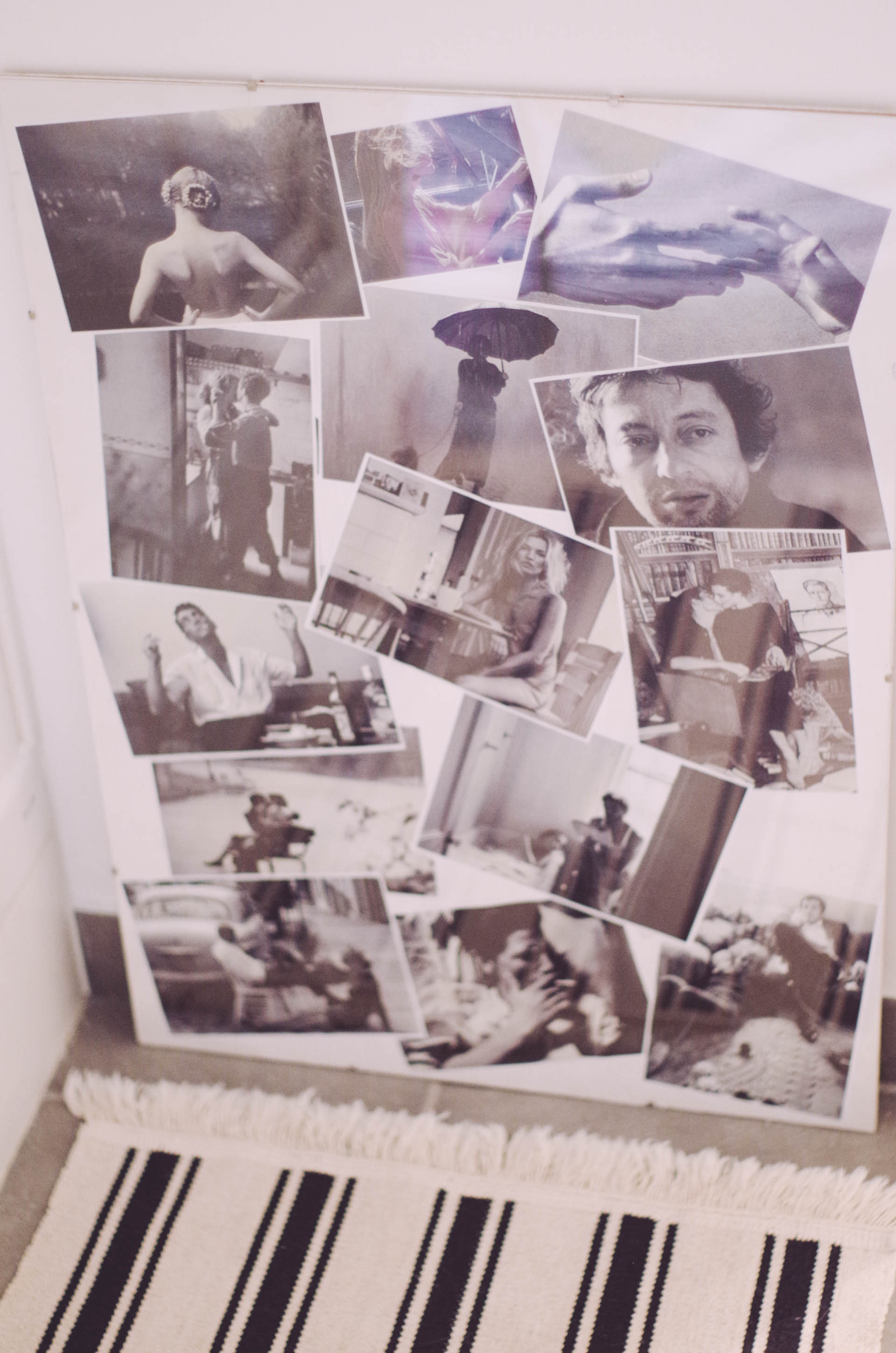

From the living room we move into the bedroom which also serves as boudoir. On the vanity table I recognise the black boxes in which she packs the jewellery pieces from her website, and right next to them, a frame with one of my line paintings, a gift from me to Diana. It feels good to see it here, among the most precious objects in her possession, her jewellery cases, which to her also act like memory boxes.

“For many years now, I bought jewellery to remind me of something dear to my soul or simply as a gesture of self-appreciation. I really hope and wish that women have plenty of jewellery in their boudoir as proof of the happiness in their life.”

There are other frames, in the bedroom, on the hallway, even in the toilet with beautiful, artistic photographs, that get my attention as we move around. More gifts from her friends involved with the arts or just personal preferences. A male nude photograph above the toilet makes me smile in particular, only because I also happen to have a male nude image above my toilet at home, a painting I made myself.

“It’s a self-portrait of a friend of mine, a photographer,” she says about the nude. “I got it as a gift.”

“How brave of your friend,” I say.

There is still some light left, so we head for the walk outside, with the intention to take a few more photos. For this, she puts on a long white coat accessorised with a white flower brooch, a black leather ribbon in her hair, a black cube purse on her arm, and a pair of wedge boots, also black. As we step outside, among cranes, barges, and skyscrapers, it’s almost impossible to reconcile Diana’s elegance with the rough Rotterdam aesthetic.

She admits that Rotterdam is not exactly her cup of tea. “Too industrial and too quiet.” There are, however, certain areas which she really likes, such as the historical and more classical looking Delfshaven - where she is now taking me, because “it’s beautiful” and “it reminds me of Amsterdam” - the Cool district for its cafes and places to hang out, the artsy Museumplein, and definitely the nature, such as the park around the corner from where she lives, Het Park, and Kralingse Bos, by the lake.

“Compared to Amsterdam, it does seem like a more calm and accessible city, which makes life easy. But it lacks the charm of the capital, it is less vibrant, and the people living here are less sophisticated in terms of looks and display less preoccupation with beauty compared to Amsterdammers.”

Delfshaven is a first for me, although I have been to Rotterdam countless times before. Indeed, it is Amsterdam-pretty. And it looks charming in the pink, sunset light, with steam rising from the houseboats moored along the canal. The air is chilly and smells like burnt wood, signs that winter is close. Once again I realise that this city is waiting to be discovered, it doesn’t show itself off. You just need to know where to go.

On the way back to the apartment, I want to take a photo of Diana against what I consider to be the real Rotterdam, the city of cranes, cargo boats, and skyscrapers.

“You like industrial architecture, don’t you?” she says.

“I do. It comforts me. And I think it perfectly matches the spirit of Rotterdam, the harbour city. I wish Amsterdam were more like this.”

Diana is back to her comfortable heels and leggings, and since it’s dinner time she puts on a festive silvery top instead of the white shirt, accessorised with the Heritage silver necklace and ring.

“Of course I’m always dressed-up like this when I cook. Always.” We laugh and feel more relaxed now that the photoshoot is over.

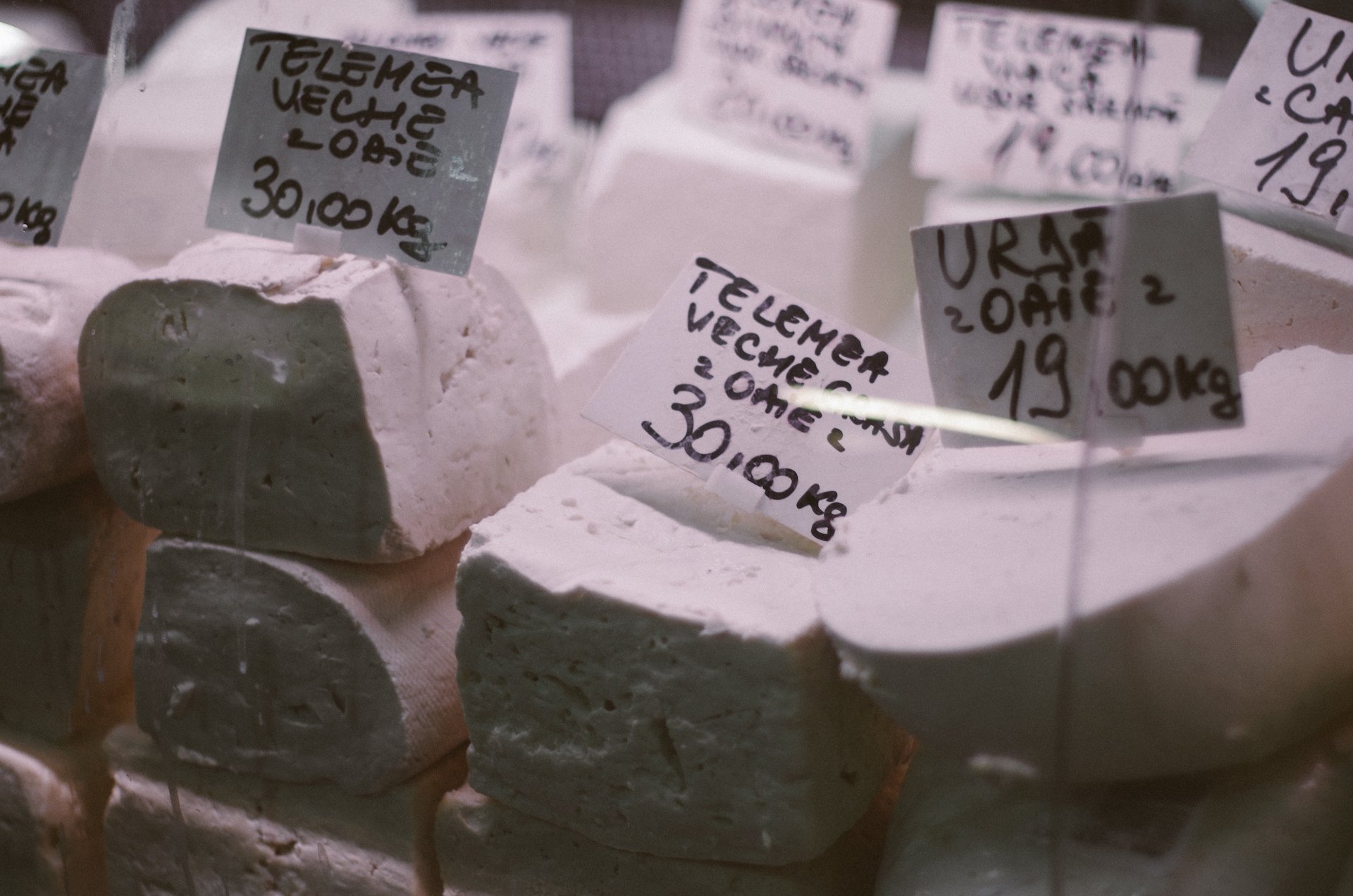

Our boyfriends join us for dinner. Diana cooks salmon and vegetables, and before that we have cheese - “four different types, all from Greece,” Kosta explains and proceeds to name them - and olives, most certainly from Greece too. Indeed, from Kalamata, comes the confirmation.

“What else is from Greece?”, I say. “Besides you, the furniture, the food, the radio station…”

It turns out there is more. There are also Greek television channels, and everything you need in order to prepare a Freddo espresso, which to me looks like a smaller frappe without the milk. And perhaps it is more.

“I like these things,“ Kosta explains. “I am used to them, they bring me comfort, but this is not about me being proud of my Greekness. They’re just habits.” And then, looking at my boyfriend, who has just mentioned the latest dish he prepared at home: “But do you know what makes me really proud? To know that an English guy cooks a Greek moussaka in his home in Amsterdam. That makes me very proud.”

I am thinking that, as much as this is a glimpse into Diana’s fresh life in the Netherlands - and a bit of Kosta’s life, too - it can be representative for the expat experience in general, in any other country. We expats do live in a bubble, and it is important how we cultivate it and who we bring into the bubble with us. Our bubble becomes our home, our family, and to some extent, ourselves. We are a bit reborn each time we move and create a new life.

I am sure Diana’s life in the Netherlands will grow into something as memorable as the others she has had so far. Besides, she is proof that dreams have no borders. They can be pursued everywhere.

Diana’s favourite addresses in Rotterdam:

For coffee:

Studio Unfolded (also for ceramics)

For flowers:

For clothes:

For everything cool:

The shops around the Markthal